In Babbage's time, printed mathematical tables were calculated by human computers; in other words, by hand. They were central to navigation, science and engineering, as well as mathematics. Mistakes were known to occur in transcription as well as calculation.[53]

At Cambridge, Babbage saw the fallibility of this process, and the opportunity of adding mechanisation into its management. His own account of his path towards mechanical computation references a particular occasion:

In 1812 he was sitting in his rooms in the Analytical Society looking at a table of logarithms, which he knew to be full of mistakes, when the idea occurred to him of computing all tabular functions by machinery. The French government had produced several tables by a new method. Three or four of their mathematicians decided how to compute the tables, half a dozen more broke down the operations into simple stages, and the work itself, which was restricted to addition and subtraction, was done by eighty computers who knew only these two arithmetical processes. Here, for the first time, mass production was applied to arithmetic, and Babbage was seized by the idea that the labours of the unskilled computers [people] could be taken over completely by machinery which would be quicker and more reliable.[151]

There was another period, seven years later, when his interest was aroused by the issues around computation of mathematical tables. The French official initiative by Gaspard de Prony, and its problems of implementation, were familiar to him. After the Napoleonic Wars came to a close, scientific contacts were renewed on the level of personal contact: in 1819 Charles Blagden was in Paris looking into the printing of the stalled de Prony project, and lobbying for the support of the Royal Society. In works of the 1820s and 1830s, Babbage referred in detail to de Prony's project.[152][153]

Difference engine

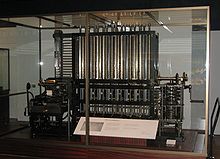

Babbage began in 1822 with what he called the difference engine, made to compute values of polynomial functions. It was created to calculate a series of values automatically. By using the method of finite differences, it was possible to avoid the need for multiplication and division.[154]

For a prototype difference engine, Babbage brought in Joseph Clement to implement the design, in 1823. Clement worked to high standards, but his machine tools were particularly elaborate. Under the standard terms of business of the time, he could charge for their construction, and would also own them. He and Babbage fell out over costs around 1831.[155]

Some parts of the prototype survive in the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford.[156] This prototype evolved into the "first difference engine". It remained unfinished and the finished portion is located at the Science Museum in London. This first difference engine would have been composed of around 25,000 parts, weighed fifteen short tons (13,600 kg), and would have been 8 ft (2.4 m) tall. Although Babbage received ample funding for the project, it was never completed. He later (1847–1849) produced detailed drawings for an improved version,"Difference Engine No. 2", but did not receive funding from the British government. His design was finally constructed in 1989–1991, using his plans and 19th-century manufacturing tolerances. It performed its first calculation at the Science Museum, London, returning results to 31 digits.[citation needed]

Nine years later, in 2000, the Science Museum completed the printer Babbage had designed for the difference engine.[157]

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "1top-oldtattoo-2" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to 1top-oldtattoo-2+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/1top-oldtattoo-2/CALML-R2zGCPobNj%3DXreQ3drQv35C3d9nOti%2B7s9PgFKzELKSag%40mail.gmail.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment